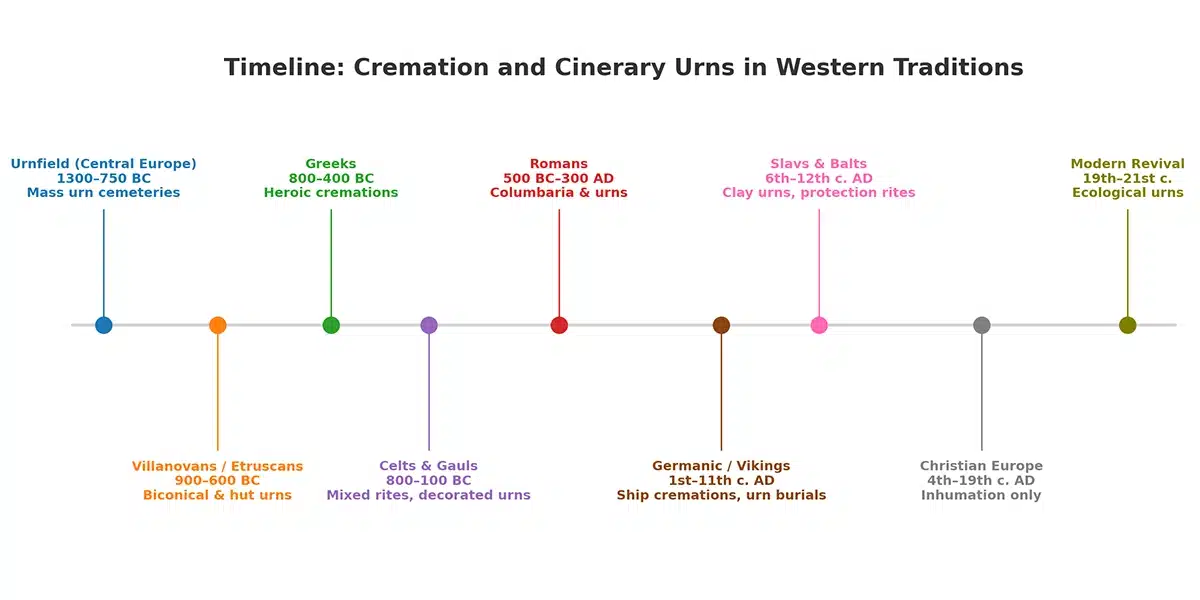

📖 Introduction

Cremation is one of the oldest funerary rites known to humanity.

From its earliest appearances, it has been accompanied by the funerary urn, or cinerary urn, which soon became much more than a container: a spiritual, social, and cultural symbol.

This dossier traces the evolution of cremation and funerary urns in the Western world, from prehistory to the modern era, highlighting not only the practices themselves but also the underlying motivations that shaped them.

🔥 1. Prehistoric Roots and the Urnfield Culture (20,000 – 750 BC)

The story of cremation in Western traditions begins long before written history.

-

In the Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic (20,000–10,000 BC), we find the first sporadic traces of cremation in Europe. These were rare and isolated, but they show that fire was already linked to death as a powerful force of transformation.

-

By the Neolithic and Bronze Age (6,000–1,200 BC), cremation became more frequent. Ashes were sometimes gathered in simple pits or placed in rudimentary containers — the very first ancestors of what would later become the funerary urn.

-

The practice reached a turning point with the Urnfield Culture (c. 1300–750 BC) in Central Europe. Here, cremation was fully systematized. The ashes of the dead were placed in standardized cinerary urns and buried together in vast cemeteries. It is from these fields of urns that archaeologists gave the culture its name: Urnfield.

👉 For the first time in European history, the funerary urn became not just a practical container, but a symbol of collective memory. The urn stood for purification by fire, and at the same time, for the desire to preserve a permanent and organized trace of the dead within the community.

🏺 2. Villanovans and the Etruscan Origins (9th–6th c. BC)

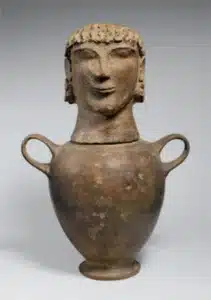

The Villanovans, considered the proto-Etruscans, systematized cremation as the main funerary rite. The ashes of the deceased were placed in biconical cinerary urns, simple yet codified containers made of impasto pottery. Another distinctive form was the hut urn (urna a capanna), modeled after the domestic house. These urns reflected the belief that death was not an end but a continuation of life in another dwelling.

As the Villanovan culture evolved into the historical Etruscans, funerary practices gradually shifted. From the 8th century BC, inhumation began to replace cremation, and tombs became monumental, carved into rock and richly decorated. Yet the use of urns did not vanish: the Etruscans developed anthropomorphic cinerary urns, sometimes representing the features of the deceased, and created elaborate sarcophagi, such as the famous Sarcophagus of the Spouses.

-

Motivation: Cremation and the use of cinerary urns were part of a structured ritual of ancestry and social identity.

-

The biconical urn symbolized ritual order.

-

The hut urn directly linked the house of the living with the house of the dead, embodying the idea of domestic continuity after death.

-

Later, under Greek influence, the shift toward inhumation reflected a new conception: the tomb as a “house of the afterlife” rather than a container for ashes.

👉 The Villanovans and Etruscans did not invent cremation, but they created a symbolic and architectural system around it, in which the urn was not just a vessel but a representation of memory, family lineage, and cultural values.

🏛️ 3. Greeks and Heroic Cremation (8th–4th c. BC)

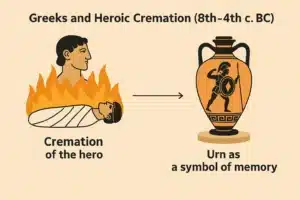

In Homeric Greece, cremation was regarded as the supreme honor for a warrior. In the Iliad, both Patroclus and Achilles are burned on grand funeral pyres, their ashes carefully collected and preserved. Fire was seen as a way to sublimate the body and elevate the soul toward the gods.

The ashes were often placed in urns, accompanied by grave goods such as weapons, armor, or personal objects. These urns were not only containers but symbols of courage and heroic memory, perpetuating the honor of the deceased within the community.

From the Classical period onward, funerary practices became more diverse. Across much of Greece, inhumation gradually replaced cremation, reflecting a growing belief in the importance of preserving bodily integrity for the journey to the underworld.

👉 Athens, however, was a major exception. According to Toohey (Death and Burial in the Ancient World, p. 365), the Athenians normally cremated their dead and placed the ashes in an urn. Archaeological evidence from the Kerameikos cemetery confirms this tradition. Cremation in Athens carried both a civic and commemorative dimension, linking the individual to the polis.

Thus, while many Greek regions turned to inhumation, Athens maintained cremation as a civic norm, making the urn a visible marker of belonging and remembrance.

👉 For the Greeks, and especially the Athenians, cremation was tied not only to heroic ideals but also to the identity of the community, transforming death into both personal glory and civic memory.

🇮🇹 4. Rome and the Universalization of Cinerary Urns (5th c. BC – 3rd c. AD)

In early Rome, both inhumation and cremation coexisted, reflecting a diversity of traditions. But from the Republican period onward, and especially during the early Empire, cremation became the dominant funerary rite.

The ashes of the deceased were collected in cinerary urns, crafted from materials that reflected social status: from simple clay for the modest, to marble, glass, or bronze for the wealthy elite. These urns were often placed in collective funerary buildings known as columbaria, with hundreds of niches resembling dovecotes — a practical solution for the crowded capital.

For the Romans, cremation was more than a private ritual: it was a civic and social act. The urn did not just preserve the ashes; it expressed the identity, lineage, and prestige of the deceased. Inscriptions and decorations turned many urns into monuments of memory, transmitting family honor across generations.

By the 3rd century AD, however, the practice shifted again. Influenced by new religious and cultural ideas — including Christianity’s emphasis on bodily resurrection — inhumation became the norm, and cremation was gradually abandoned.

👉 Rome played a crucial role in spreading the tradition of cinerary urns across the Mediterranean, leaving behind an immense archaeological heritage of urns, columbaria, and funerary art.

🍀 5. Celts and Gauls (Iron Age Europe, 8th–1st c. BC)

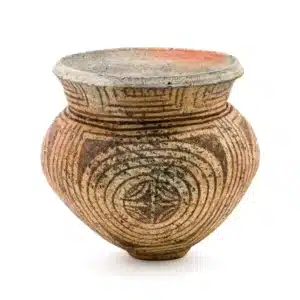

Among the Celts and Gauls, funerary practices varied widely. Some tribes favored cremation, depositing ashes in urns or amphorae, often richly decorated. Others practiced inhumation, showing the coexistence of multiple beliefs about death and the afterlife.

For many Celtic groups, fire was a passageway to the other world. Cremation symbolized the release of the spirit, while the urn preserved a tangible link to the clan and the land. Decoration on the urn often reflected the status or tribal affiliation of the deceased.

👉 Celtic funerary culture thus balanced spiritual liberation with communal memory, blending diversity with a shared belief in continuity beyond death.

⚔️ 6. Germanic Peoples and Vikings (1st millennium AD)

Among Germanic tribes, cremation was the dominant practice before Christianization. For them, fire was a force of transformation, ensuring the safe passage of the soul.

The Vikings (8th–11th c.) brought cremation to its most striking expression. Funeral pyres were sometimes built on ships: the deceased, surrounded by weapons and treasures, was burned and sent adrift or buried beneath a mound. Ashes might be placed in urns or scattered within the tumulus.

👉 Viking cremation combined fire, ships, and urns into one of the most powerful symbolic rites of Europe, expressing death as a journey toward Valhalla or the realm of Hel.

🛡️ 7. Slavs and Balts (6th–12th c.)

For early Slavic peoples, cremation was widespread, with ashes often placed in simple clay urns buried in flat cemeteries. One key motivation was protective: the fire ensured that the dead would not return as restless spirits.

Among the Balts (Lithuanians and Latvians), cremation endured even longer, well into the medieval era. Here it carried a cosmic meaning: fire and the sun were seen as forces that purified the soul and restored it to the universal order.

👉 Slavic and Baltic cremation thus expressed both protection for the living and a cosmic vision of purification.

✝️ 8. Christianity and the Decline of Cremation (4th–19th c.)

With the rise of Christianity, cremation was gradually forbidden. The doctrine of bodily resurrection required that the body remain intact for the Last Judgment. Cremation became a taboo, sometimes associated with paganism or heresy.

As a result, urns disappeared almost completely from Western Europe for over a thousand years. Only in some peripheral pagan traditions (Slavic, Baltic, Scandinavian) did they survive until Christianization was complete.

👉 Christianity nearly erased the cinerary urn tradition from Western memory.

🌍 9. Modern Revival (19th–21st c.)

The modern revival of cremation began in the 19th century. Urbanization and overcrowded cemeteries led reformers to promote cremation for hygienic and rational reasons. The first modern crematorium opened in Milan in 1876, followed soon by Paris, London, and Berlin.

In the 20th century, cinerary urns returned in artistic forms — marble, metal, glass — before evolving into today’s ecological urns: biodegradable materials, tree-urns, and other personalized vessels.

Today, cremation is chosen for diverse reasons: philosophical, ecological, or spiritual. The urn has become once again a central object of memory, but one that reflects individuality and choice.

✨ Conclusion

From the first clay urns of the Bronze Age to today’s biodegradable urns, the history of cremation and funerary urns in the Western world reveals three constant human needs:

- To purify and transform the body through fire.

- To preserve a trace of the deceased in an urn as a material memory.

- To connect the living and the dead through ritual, symbols, and shared belief.

👉 The urn has never been just a container. It is a bridge between worlds, a vessel of memory, and a timeless symbol of humanity’s search for meaning in death.

0 Comments