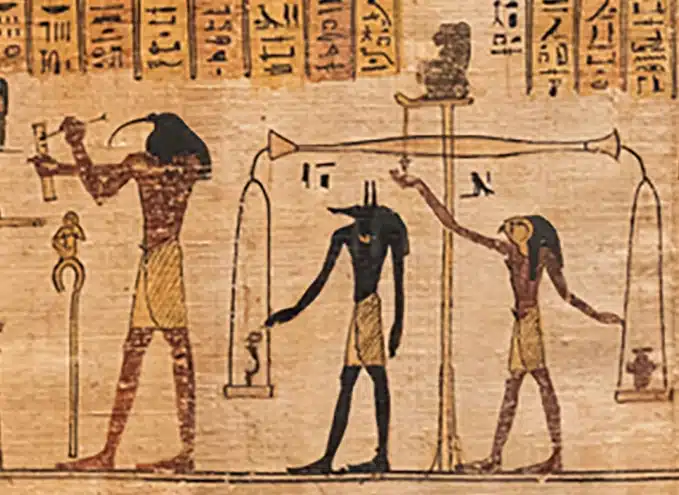

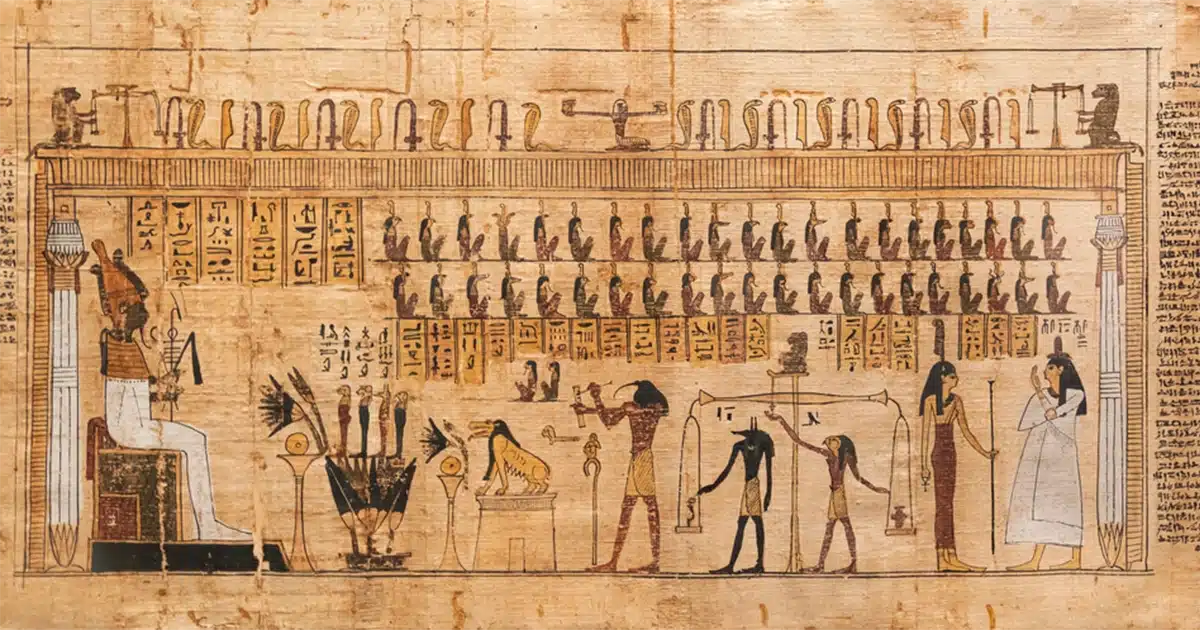

*Photo: The weighing of the heart in the tribunal of Osiris: a key moment where the heart is compared to the feather of Maat

Introduction

How can we draw inspiration from the wisdom of ancient Egypt to live more fully today? The Egyptians saw death not as an end, but as a passage — a step into eternity. Their entire culture was built on the idea that accepting death and preparing for it harmoniously allowed one to live with freedom, serenity, and purpose.

To them, life and death were not opposites but companions, bound together by the principle of Ma’at, the cosmic order of truth and balance. In learning from their vision, we may discover that embracing mortality does not diminish life — it enriches it, giving each moment depth and meaning.

1. Death as a Passage, Life as Preparation

For the Egyptians, death was not a brutal rupture but a passage into another mode of existence. To die did not mean to disappear: it meant to enter eternity. Tombs, sarcophagi, and funerary rituals were not mere customs: they were houses of eternity, designed to ensure the continuity of being in the other world.

Suggested image: A papyrus from the Book of the Dead showing the deceased guided toward the afterlife.

2. Ma’at: The Truth that Liberates the Soul

At the heart of this vision lies Ma’at. Both goddess and cosmic principle, she embodied order, justice, and harmony in the world. To live according to Ma’at was to live in tune with the universe.

At the moment of judgment, the heart of the deceased was placed on a scale opposite the feather of Ma’at. If it was light, the soul was reborn in the afterlife. If it was heavy, it was extinguished. Thus, an entire existence was a school of truth and balance, where every choice prepared the soul for its liberation.

Suggested image: The famous scene of the Weighing of the Heart, with Anubis, Thoth, and the feather of Ma’at.

3. Preparing for Death to Live Better

This constant attention to the afterlife was not a morbid obsession, but a way of giving meaning to earthly life. Tombs, decorated sarcophagi, offerings, and the prayers inscribed in the Book of the Dead all served the same purpose: to ensure the survival of the soul.

To accept death meant not to fear it—and thus to live more freely. For the Egyptians, death was an awaited destination, and life a confident preparation.

Suggested image: Interior of a richly painted tomb with hieroglyphs and offerings.

4. The Order of the Cosmos Carved in Stone

Even architecture and mathematics expressed this spiritual quest. The pyramids, with their carefully calculated proportions and their orientation to the stars, reflected a greater truth: universal order.

To build in harmony with the cosmos was already to prepare the soul for its place in eternity. The balance of lines and the precision of measures became a silent prayer, a way to inscribe Ma’at into the earthly world.

Suggested image: The pyramids of Giza seen from above, showing their geometric alignment with the landscape and stars.

5. Living in Accord with Death, to Be Reborn

Behind these grand monuments and complex rituals lies a simple idea: to accept death is to give oneself the chance to be reborn.

The Egyptians did not spend their lives fearing the end: they prepared for it with serenity, convinced that this preparation freed the soul. For them, eternity began here and now, in every act aligned with Ma’at. And it was this peaceful acceptance of death that made life fuller, more alive.

Anubis guides the deceased to judgment – Thoth notes the result balance between truth and lies

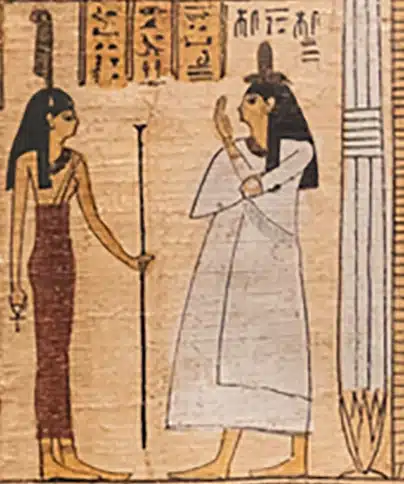

Maat personified justice, order, cosmic balance

| God/Goddess | Representation | Role | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | Falcon-headed, sun disk | Sun god, creator, supreme deity | Sun disk |

| Osiris | Mummified man, green skin | God of afterlife, resurrection, fertility | Crook & flail |

| Isis | Woman with throne-shaped crown | Goddess of magic, motherhood, healing | Throne crown |

| Nephthys | Woman with house + basket on head | Goddess of night, mourning, protection of the dead | Night sky |

| Horus | Falcon-headed man | God of kingship, sky, protection | Eye of Horus |

| Seth | Man with Seth-animal head | God of chaos, storms, violence | Storm |

| Anubis | Jackal-headed man | God of mummification, guardian of the dead | Scales |

| Thoth | Ibis-headed man or baboon | God of wisdom, writing, knowledge | Papyrus scroll |

| Ma’at | Woman with ostrich feather | Goddess of truth, balance, cosmic order | Feather |

| Hathor | Woman with cow horns & sun disk | Goddess of love, beauty, music | Sistrum |

| Sekhmet | Lion-headed woman | Goddess of war, destruction, healing | Lion |

| Ptah | Mummified man with blue cap | God of craftsmen, creation, architecture | Staff of Ptah |

| Amun | Man with tall plumed crown | God of hidden power, later merged with Ra | Wind / double plume |

| Sobek | Crocodile-headed man | God of Nile, strength, fertility | Crocodile |

| Bastet | Cat-headed woman | Goddess of home, fertility, protection | Cat |

In Egyptian mythology, the gods were often defined through opposites and complementary forces. This reflected the Egyptian belief that the universe itself was held in balance — light and darkness, order and chaos, creation and destruction. To understand these divine pairs is to glimpse the logic of Ma’at, where harmony arises not from denying opposites but from keeping them in equilibrium.

Gods in Balance: Opposites and Complements in Egyptian Mythology

Note: Isfet is not a worshipped god but the principle opposed to Ma’at (disorder/untruth), often personified by the serpent Apophis.

👉 Read : Cremation and Funerary Urns in Western Traditions

FAQ — Ancient Egypt, Ma’at, and the “weighing of the heart”

What is the “weighing of the heart” in the tribunal of Osiris?

It is the moment of judgement where the heart of the deceased is weighed against the feather of Ma’at (truth and balance). A heart “light” with truth passes into the afterlife; a “heavy” heart fails to attain renewal.

Who or what is Ma’at?

Ma’at is both a goddess and a cosmic principle—truth, justice, harmony, and right order. Living “in Ma’at” means aligning one’s actions with balance in self, society, and cosmos.

Did Egyptians see death as an end?

No. Death was a passage to another mode of existence. Tombs, rites, and texts (like the Book of the Dead) were ways to prepare the soul for continuity beyond death.

How does this vision help us live better today?

By acknowledging mortality and practising inner balance, we reduce fear and live more intentionally: clearer priorities, calmer choices, and a deeper sense of purpose.

Why are pyramids and sacred geometry mentioned?

Their design and star alignment expressed a search for universal order. Building in harmony with the cosmos symbolised inscribing Ma’at—balance—into earthly life.

Is Ma’at opposed to a “cult of place” or idol worship?

Ma’at is about right relation and living truth, not attachment to an object or spot. Monuments served a passage; the aim was alignment and renewal, not clinging.

What images suit this article?

A papyrus scene of the weighing of the heart (Anubis, Thoth, feather of Ma’at), interior of a painted tomb with offerings, and an aerial view of the Giza pyramids showing geometric alignment.

How can I practise a Ma’at-inspired approach now?

Seek balance in choices, tell the truth, prepare calmly for endings, and favour meaningful rites that help you let go—treating death as a teacher for living well.

0 Comments